Bloomberg UK | Jobs Report

7 Sep 2023

Elite university towns provide a blueprint for growth in the ‘knowledge economy.’

Cambridge has opened a decisive lead over its rival Oxford in creating more jobs, providing a road map for other cities seeking to replicate the work Britain’s top two university towns deliver in stimulating the local economy.

By Lucy White, Andre Tartar, Alexander Mortimer and Madeleine Parker

Using Reed Recruitment’s job vacancy data, Bloomberg will produce monthly readouts on the state of the jobs market in England.

With students returning to classes this month, the eight-century-long rivalry between Britain’s oldest universities is coming into sharper view. Data from Reed Recruitment, analyzed by Bloomberg, shows Cambridge has the edge against Oxford in terms of the number of job openings available per worker.

Both are well above the average across England, suggesting that Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government could learn much from the educational centers in his goal to deliver growth through a “knowledge economy” in time for the general election expected next year. Employment experts and investors warn that Brexit, strict immigration policies, a lack of public investment and incentives for start-ups abroad risk destabilizing the success of Britain’s two biggest hubs for innovation and learning.

“Both Oxford and Cambridge have a rich history of academic excellence and innovation, and this has naturally spilled over into their local economies,” said James Reed, chairman of Reed. “The success of these cities demonstrates the potential for universities to play a significant role in local economic development.”

The Oxbridge Attraction

For workers searching for a job, Cambridge and Oxford have typically been reliable hunting grounds for the past several years. Reed’s data, stretching back to 2018, shows the number of vacancies per 10,000 workers in Oxford has typically been around 140% higher than the national average, while in Cambridge that extends to 270%.

Like most of the country, though, both university towns have seen a significant decline in job postings over the last year with a broader economic slowdown.

On wages offered, the picture differs slightly. Positions in Cambridge have typically carried a salary that’s a few thousand pounds above the national average. Oxford’s pay advantage has been less consistent, recently catching up to Cambridge after lagging for a few years.

Corporate giants such as GSK Plc, AstraZeneca Plc and BMW AG have chosen to locate major research centers and plants in Oxford and Cambridge, taking advantage of the talent flowing out of their prestigious universities and the close proximity of both to London.

In Oxford, “we’re seeing some international institutions who want to move in because they want to be part of the ecosystem here,” says Anna Strongman, chief executive officer of Oxford University Development, a joint enterprise between the university and pensions investor Legal & General Group Plc to develop new facilities in the city.

It isn’t just established businesses generating jobs in Oxbridge, as the two universities are collectively known. Both are under pressure to commercialize the research they develop and are now churning out start-up companies — Oxford slightly outpacing its rival.

A report from data company Beauhurst earlier this year found the University of Oxford was responsible for 205 spin-outs since 2011, topping the table and ahead of the 145 that came from the University of Cambridge.

“Oxford Science Enterprise, the venture capital organization which invests in Oxford spin outs, has had a really successful capital raise and is investing in a whole new wave of companies,” Strongman said. “They all want to be located close to the university because it’s part of their networks.”

Jonathan Hart-Smith, CEO of the technical recruitment company CK Group, said both cities are “very good at encouraging people who’ve created some intellectual property in their PhD.”

“Whether it’s a spin-out from Cambridge or a spin-out from Oxford, the first place they go to are the professors or the departments they already know” to find new staff, he said.

The entrepreneurialism that the universities breed also rubs off. “You have companies who have just grown here as part of the ecosystem, but without having been spun out directly from the university,” said Dan Thorp, CEO of the business group Cambridge Ahead.

Aerospace firm Marshall of Cambridge, for example, “started four generations ago by someone working as a caterer in one of the colleges and decided to start a car chauffeuring business,” Thorp said.

The success of Oxford and Cambridge isn’t just due to the universities, Reed added. “Incentives for innovation, the creation of entrepreneurial clusters, and the encouragement of new businesses have all played crucial roles,” he said.

That bustling start-up environment is attracting more investment to the cities. Legal & General has invested in a swathe of projects across both cities, including Oxford’s £200 million Life & Mind Building and the construction decarbonisation firm Cambridge Electric Cement, founded by three academics.

Oxford and Cambridge are “world class universities, and as an organization that invests in the built environment, we see the opportunity for innovation, job growth, productivity coming out of those universities to be much greater than it is,” says Bill Hughes, global head of real assets at L&G Investment Management.

While Oxford and Cambridge may be thriving compared to other UK cities, he adds, the economic productivity and job growth which they generate is well behind comparative university cities in the US. “That’s why it’s an opportunity,” he says.

Other nearby towns and cities could reap the rewards too. Abingdon, Milton Keynes, Bedford and Kidlington — situated along the so-called “varsity corridor” connecting Oxford and Cambridge — all have job postings well above the England average.

Housing markets in that corridor are “more accessible because Oxford is one of the most unaffordable places in the UK,” says Strongman. She noted many people work in Oxford but live in Bicester or Milton Keynes.

Cambridge’s Edge

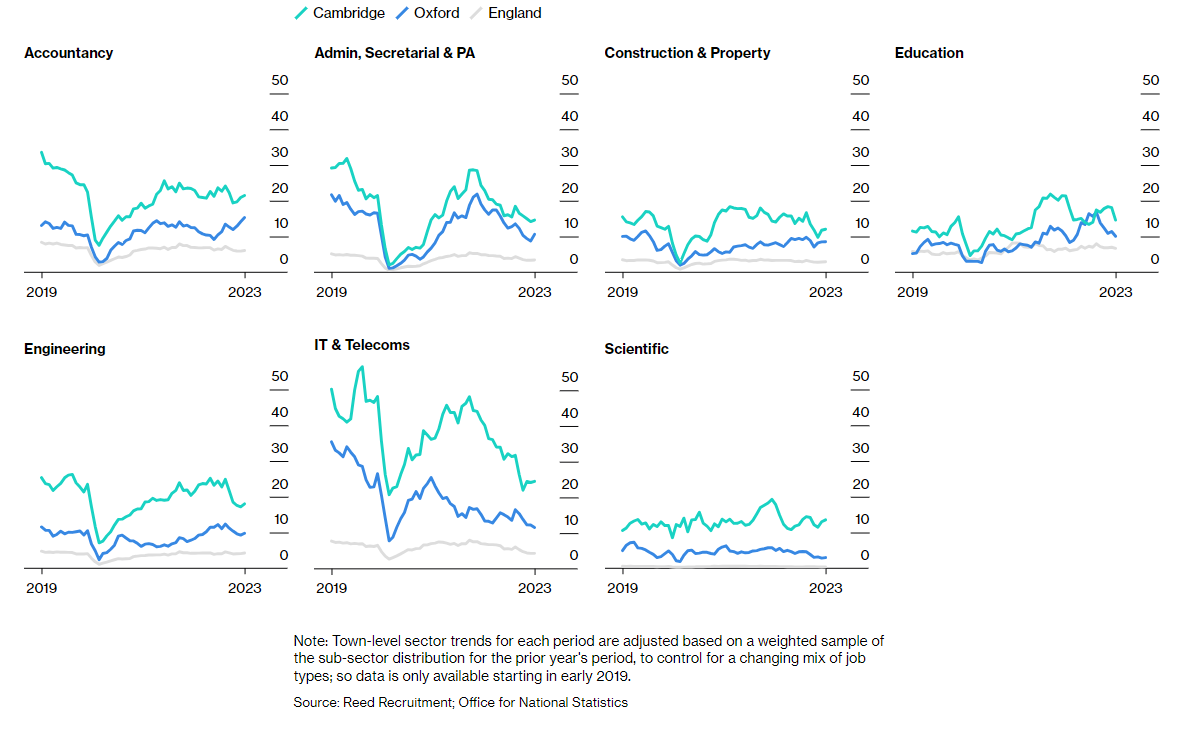

Cambridge itself has been cultivating a niche in biotechnology and life sciences, which is now being reflected in the jobs data. The city’s job vacancies in sectors such as science, IT and engineering far outpace those both in Oxford and the England average, according to Reed’s data.

“When you look globally at which ecosystems are developing IP-rich, deep tech and life sciences companies, the top three in the world are the Bay Area in the US, the Boston area on the east coast of the US, and Cambridge,” says Michael Anstey, partner at Cambridge Innovation Capital.

IT and Engineering Drive Cambridge Jobs Market

Job postings per 10,000 workers, 3-month trailing period

Openings in these lucrative industries may go some way to explaining why the wages on newly offered jobs have typically been higher in Cambridge than its rival down the road. Anstey, who formerly worked at Oxford Capital Partners, thinks Cambridge has a “slightly more mature ecosystem when it comes to innovation than Oxford,” as it has been “focusing on entrepreneurship for a bit longer.”

More broadly, Strongman notes Oxford is facing demographic issues that haven’t hit Cambridge in the same way. “From 2000 to 2021, Oxford’s population is aging quicker than Cambridge’s is,” she says. “That’s really because Cambridge has built more housing within the city, and it’s built more science space effectively for these spin-outs. Oxford now has got to catch up by creating the infrastructure to enable this growth to happen.”

Cambridge’s building efforts have also enticed Microsoft Corp. to open a location in Cambridge. Strongman says Oxford has no “big tech” occupants and only one Grade A office space.

A Warning for the Future

Oxford’s star is now on the ascendant, with L&G committing to a major investment project in the city. But experts in both Oxford and Cambridge are keen to point out that Britain’s exit from the European Union, and the end of free movement in particular, has been a setback.

Cambridge is a “very cosmopolitan, open city that’s drawing on talent from around the world,” said Daniel Zeichner, the Labour member of Parliament representing the area. “Future success isn’t guaranteed unless you make the right decisions.”

The spin-outs being generated in the universities could depart if they find the business environment in the UK too harsh. “There is an assumption that if people don’t stay in Oxford, they’ll just go a bit further out or go to London,” Strongman said. “But the spin-out businesses will go to Boston or San Francisco.”